Born 1941, Jutta Brückner studied political science, philosophy and

history (Ph.D.). She has had no formal training in film, and also scripts

for Völker Schlöndorff and Ula Stöckl.

Born 1941, Jutta Brückner studied political science, philosophy and

history (Ph.D.). She has had no formal training in film, and also scripts

for Völker Schlöndorff and Ula Stöckl.

As to a particular relation between feminism and film form: woman's historical

and cultural oppression does not just reveal itself not only in our familiar

exclusion from the forms of exchange in a public sphere erected by men.

Also it especially reveals itself in the deformation, renunciation and

incapacitation of our physical integrity and perception. This has most

clearly affected sexuality, but also looking. Through the look, a person

establishes space relations, and without space there is no time. Space-time-looking

mean something else to women than to men. In film especially, these three

elements of perception come together. Moreover, film allows us women to

represent our disrupted physical integrity, whereas literature restricts

physical presence to the imagination. In filmic representation, a vision

of what undisrupted physical integrity might be emerges. And that vision

presents itself not only to our imagination but also to our looking. Film

for me offers the sole medium in which we can explore our collective labor

of mourning for the cultural paralyzing of our bodies, our eyes, and our

space-time relations. The goal: recuperating the means to reconstruct

symbolically. This throws into question filming's own premises. Film becomes

filming’s content, not as the burden or joy of a tradition, within

which you are confined to sitting for hours in movie theatres. It’s

not as "real life," the way the French New Wave formulated it.

I mean recuperating our capacity to look.

This has nothing to do with a specific style. There is no one feminist

style. Nor can stylistic "innovations" be introduced like exotic

commodities or clothes fashions. I am talking about new questions and

new points of departure.

My films are all autobiographical. Autobiographical motivations counter

the false generalizations into which we have been molded for years. These

generalizations are false for men too; they simply don't realize it. We

women tend to notice them more because our individuality simply cannot

be contained within these generalizations. We must not just constitute

images out of the small banalities of daily life. To do only that is false

realism. Rather, we must find new forms to narrate private life, to recognize

collective gestures in the most banal ones. For example, the way a wife

hands her husband a cup of tea in the morning. To what extent does this

collective gesture destroy me because it has nothing to do with me and

makes me into a trained dog? I am trying to disrupt the habitual ways

in which people see.

copyright Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 1982, 2005

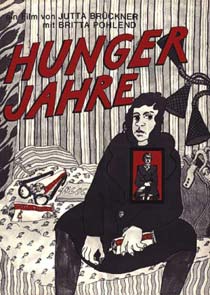

HUNGERJAHRE (YEARS OF HUNGER)

1979, 100 min, 35mm, b/w, dist: Basis Film (Berlin)

Primé à Sceaux 1980, Festival du Film de Femmes (Bruxelles)

1981

Set in the sexually and politically restrictive fifties, the film reconstructs

the memories of an adolescent girl who refuses to become a woman. She

finds herself so alienated from her body and her emotions that she finally

attempts suicide.

"J'ai voulu montrer comment une jeune fille - ce qui était notre cas à toutes dans les années cinquante - arrivait déjà déformée au seuil de l'existence adulte, du fait d'un certain type d'éducation qui vous détruit et qui peut avoir une issue mortelle."

Hungerjahre

is a film about being young in the 1950s.Thirteen-year-old Ursula is the

only child of lower-middleclass parents who want to give their daughter

a better life through social advancement. The world of the adults is that

of the German postwar boom (Wirtschaftswunder): plentiful food, housing,

clothes, and the restoration of traditional values. Ursula is confronted

with the political lies of her materialist father and the sexual antagonism

of her mother. Whatever Ursula does, her mother’s anxiety follows

her everywhere, stifling her daughter’s hunger for life every step

of the way. Ursula begins a dangerous separation between her inner and

outer lives.

Hungerjahre

is a film about being young in the 1950s.Thirteen-year-old Ursula is the

only child of lower-middleclass parents who want to give their daughter

a better life through social advancement. The world of the adults is that

of the German postwar boom (Wirtschaftswunder): plentiful food, housing,

clothes, and the restoration of traditional values. Ursula is confronted

with the political lies of her materialist father and the sexual antagonism

of her mother. Whatever Ursula does, her mother’s anxiety follows

her everywhere, stifling her daughter’s hunger for life every step

of the way. Ursula begins a dangerous separation between her inner and

outer lives.

HITLER

CANTATA

HITLER

CANTATA

D 2005, 114 min, ov-vo D, st-ond E

Aspiring young composer Ursula Scheuner (Lena Lauzemis) has two passions in her life: Hitler and music. She is obsessed with the Führer and hopes to become a famous composer.

After being rejected by the music conservatory, she uses her connection with Gottlieb Just (Arnd Klawitter), a high ranking SS colonel and her fiancé, to get an assistant position to famous composer Hanns Broch (Hilmar Thate). Broch is secretly opposed to the Nazi regime and struggles with the moral dilemma of having to compose a cantata for Hitler´s 50th birthday.

At a remote Finnish estate, Hanns and Ursula are thrown together while working on the composition. They fight not only about their opposing ideologies, but also against the romantic feelings that have evolved between them and threaten to take over their lives.

"This film is about the power of music. It

demonstrates how music can become a catalyst to a higher awareness of

your surroundings and how it can make you examine your own personal convictions!"

"Hitler sells. But Jutta Brueckner does not

merely exploit the thrill of the evil. I have rarely seen a story told

in such a complex way as Jutta Brueckner does in her latest film."

has coproduced German and international movies for cinema and television

i.e Lars von Trier: Dancer in the Dark, Michael Haneke: Caché, Patrice Chéreau: Intimacy.

"HITLER CANTATA shows how much the fascist regime uses the power

of eroticism and deduction. Brueckner gives an emotional and intellectual

insight into the psychic dimension of totalitarism. This film is important."

"Jutta Brueckner's HITLER CANTATA makes us

understand the hysteria surrounding Hitler. Her analysis of the social

infantilism is ironic, but not without compassion and her glimpse on those,

who fell for the dictator, is laconic, without sentimentality."